Emily Dickinson’s work includes poems sent as valentines and birthday greetings. Some of the love poetry she wrote was to anonymous recipients, using pseudonyms to refer to herself and to whom she was writing. Three poems were addressed to someone she called “Master.”

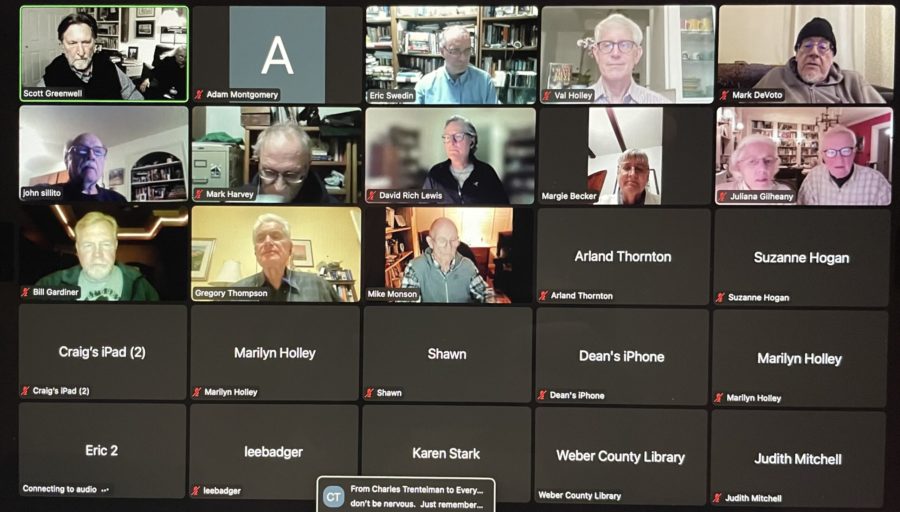

John Schwiebert, a Weber State University professor and speaker at this week’s Weber Reads series, focused his lecture both on her poetry and her likely approach to that poetry.

“She didn’t write about her poetry. . . . She didn’t leave behind instructions for her poems,” he said. “They were in handwritten form.”

The talk highlighted how transcendentalism, focusing on Ralph Waldo Emerson’s approach to it, affected Dickinson’s writing.

“Emerson’s ideas included self-trust, concentration of purpose, humility and receptivity,” Schwiebert said.

Schwiebert said he believes Dickinson also followed Emerson’s advice to record the first thought instead of suppress it. He said this helped develop her identity.

“Even if the whole world is against her,” Schwiebert said, “she is still strong, upright. She develops a strong personal identity.”

Dickinson’s poems were originally published by her friends T.W. Higgenson and Mabel Louise Todd in 1890, edited for punctuation and word choice to be more readable for the public. It wasn’t until the 1950s that Dickinson’s poetry was published using her original marks.

“A gigantic family feud went through the courts,” Schwiebert said. “Some people had some poems and others had others in the early 1890s, in early editions up until 1955. The 1955 edition edited by Thomas Johnson was the first scholarly edition that went back to the original manuscripts and tried to reproduce her work as accurately as possible with her punctuation, capitalization and word choice.”

Schwiebert also discussed the evolution of Dickinson’s poetry.

“(The first ones) sound like a gabby, gossipy teenager,” he said. “In her 20s, they become shorter. Then they became often cryptic, with ideas run together. She might talk about an inside joke referring to a dog and then go into a poem or description of self.”

Besides Dickinson’s poetry, Schwiebert also discussed her views about how she wished to be seen by the world.

“She resisted mechanical reproductions of her face because she believed the literal image fails to capture ‘the Quick’ — the mobile living spirit — of its subject. She insisted that ‘I need more veil.’ This insistence on personal mystery is one of her defining qualities.”