Wi-Fi: everyone uses it on a near-daily basis, if not more. It’s an important and almost indispensable requirement of a student’s day-to-day life. And for students who spend more than a few hours a week on campus, it’s likely those hours are spent with at least one device connected to Weber State’s Wi-Fi.

Students who spent time on campus before the fall 2021 semester came back fresh from their summer vacations to find an unfamiliar Wi-Fi network had become the university’s new standard network across the main and satellite campuses.

Instead of logging into the familiar WSUSecure, students found the network “eduroam” populating first on their computers. And instead of logging into the network with their username and password they used on eWeber, students were suddenly required to download a network certificate that would permit them access to the network.

But what is “Wi-Fi,” anyway?

Wi-Fi is a radio signal that computers, mobile devices, tablets and other devices use to interface with the internet through an access point, like a router in someone’s house. Essentially, Wi-Fi allows your computer to send (upload) and receive (download) information from the data matrix that is the internet.

Much like the previous main network WSUSecure, eduroam, or education roaming, is a Wi-Fi network that when logged into can be used to access the internet. Founded in the mid-2000s, the service began truly moving the U.S. in 2012 after the non-profit Internet2, which delivers network services to higher education institutions, added eduroam to its network servicing options.

Internet2 was founded in 1996 with the goal to help higher education institutions access Wi-Fi after it became a commercial commodity.

“It was created as basically a university platform to help institutions kind of advance operations research and their academic mission using advanced technologies,” Associate Vice President for Trust and Identity for Internet2 Ann West said. “A bunch of CIOs got in a room and basically said we need to start our own community to advance the academic mission.”

What makes the eduroam network unique is it allows students, faculty and staff to log in to the eduroam network at any participating location across the world — this is what is known as federated roaming capabilities.

“Similar to how when you’re on T-Mobile and you go outside of T-Mobile’s area, and it roams to, let’s say, AT&T, that is the kind of capability that is there with eduroam,” Weber State Networking and Communications Manager Jonathan Karras said. “If you were to go to another institution like, say, Utah State, where they support it as well, your device would just automatically connect to their eduroam. The goal being, that if you’re a student, you have more places to access the wireless wherever you may be.”

Wi-Fi roaming works similarly to data roaming. Data roaming is when one’s device switches which access point it is using to connect to the internet after moving out of the range.

Using Karras’s example, if one was to drive into an area of Ogden where T-Mobile does not have an access point, their phone would instead look for a new access point, like perhaps an AT&T access point, to stay connected to the internet instead of simply kicking the user out of whatever they were Googling.

Wi-Fi roaming works similarly — the device will continue to try and locate access points to the internet, like a new router or Wi-Fi extender, while the user continues to use Wi-Fi. Eduroam takes this a step further.

Instead of stopping at the edge of campus where there would be no more access points when using a campus-only network, eduroam should allow for connection wherever there is an eduroam access point, meaning any eduroam-equipped campuses, including public libraries and public buildings.

While Weber did switch the network students should use this past academic year, eduroam has been available for use on campus since 2013. It was typically used by faculty who knew about it or other visiting students and faculty on WSU’s campus.

Much like any other change, it only happens when there is a push for it and the funds for it. When WSU received CARES and HEERF funds as part of the government funds distributed following the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the school utilized some of those monies to upgrade the Wi-Fi by adding the Wi-Fi certificates, which came out to about $32,000 for the next five years.

The push came after a security test on the network came back allowing bad actors to steal users’ credentials.

“The Utah System of Higher Education, USHE, is all of the universities in the state, and we get together, and we perform what’s called penetration testing,” Vice President for Information Technologies Bret Ellis said. “Penetration testing is where we get like three or four individuals from other schools to come to our campus and try to break into our campus.”

These penetration tests happen about every two years, and the last one before the Wi-Fi switch revealed a vulnerability in the campus’s Wi-Fi system.

“One of the things they were successful at, and they’re successful on many campuses, is what’s called the evil twin,” Ellis said. “Your phone is always looking for WSUSecure, and your phone is not very smart, so when it sees a router that says, ‘Hey, I’m WSUSecure,’ then it gives up information. It connects to that router with your username and password because that’s what it does.”

A certificate acts like a letter of recommendation, Karras explained. The computer presents the certificate like a letter saying that the university has validated this device, and the server recognizes it, validates it and allows the device access.

Unlike a username and password login, the certificates that WSU uses give limited access to only the Wi-Fi.

“The reason for the push for everybody was we were updating the way people connect to the Wi-Fi,” Karras said. “Instead of using usernames and passwords, we were using certificate-based authentications. It’s more secure.”

Certificates, unlike the credentials used for WSUSecure and everything else on eWeber, are only good for getting onto the eduroam network and can’t be used to log into Weber’s online systems where damage could be done to individuals, or even to the whole system if the stolen credentials were from individuals with administrative power in the system.

“We’ve tried for many years to get away from the system we were using before, and we just didn’t have the resources to do it,” Ellis said.

Eduroam is no longer just something higher institutions in Utah are moving toward, but it is something that many K-12 school districts are moving toward.

“At this point in the U.S., we have more than a thousand subscribers to this service. Those are research universities, colleges and other research organizations,” Sara Jeanes, eduroam product manager at Internet2, said. “It’s been increasingly popular with university students, and over the last few years we’ve also started moving into the K-12 space as well.”

It is supposed to be beneficial to students because of the increasing availability of the networks outside of campus spaces. In London, West said, one can almost continuously be connected to eduroam without ever needing to log back in.

In Northern Utah alone, there are 613 access points, or locations, where the eduroam network can be accessed. While there are schools like the Ogden Weber Technical College or the Ogden School District, Weber County Libraries are also places for students to log on.

“Folks can get on board in addition to their elementary schools or middle and high schools as well,” Jeanes said. “It’s really exciting that we can be part of helping folks get connectivity, especially places that might be underserved by broadband. And this can be part of it in working in collaboration with folks in particular states and in Utah as a great example in particular.”

While there might be concerns about such a wide-spread internet provider, West assures students that the privacy and security wrappers provided by eduroam don’t allow for eduroam to get students’ data.

“This is all run by a non-profit, higher education research community,” West said. “We don’t take your data. We don’t see your data. It’s very different than connecting into Xfinity or another corporate provider. Some of it is how it’s designed, but some of it is actually the organization’s consortium that runs it as well.”

As far as the student experience on the day-to-day, not much has changed.

“We didn’t really change any functionality on people in that regard. It’s just a different network they are connecting to by name,” Karras said.

The new certificate-based authentication was not the only thing that got a face lift with the funds — according to Ellis, software and physical devices were upgraded to handle the new systems.

“One of the things we tried to do at the same time was across campus we moved up a generation in Wi-Fi to make sure students had adequate Wi-Fi,” Ellis said.

Like anything else in the technological space, Wi-Fi standards are also constantly changing and updating. The previous protocols, Wi-Fi 5, were released in 2014. The newest iteration, Wi-Fi 6, was adopted in 2019 and has been branded as “High Efficiency Wi-Fi.” This upgrade was not included in the $32,000 figure to change to certificate authentication.

However, across campus there is still frustration with how the Wi-Fi is running, if a student can connect to campus or if a student can get and stay on Zoom for an entire class period.

“It is inconvenient,” Ariel Krogue, student worker at Stewart Library, said. “Depending on what building you are on campus and where you’re at in the building, if you’re in the basement versus the top floor, sometimes the Wi-Fi will just drop you all together. If you need to take a quiz, you don’t want to just get dropped from the Wi-Fi in the middle of your quiz.”

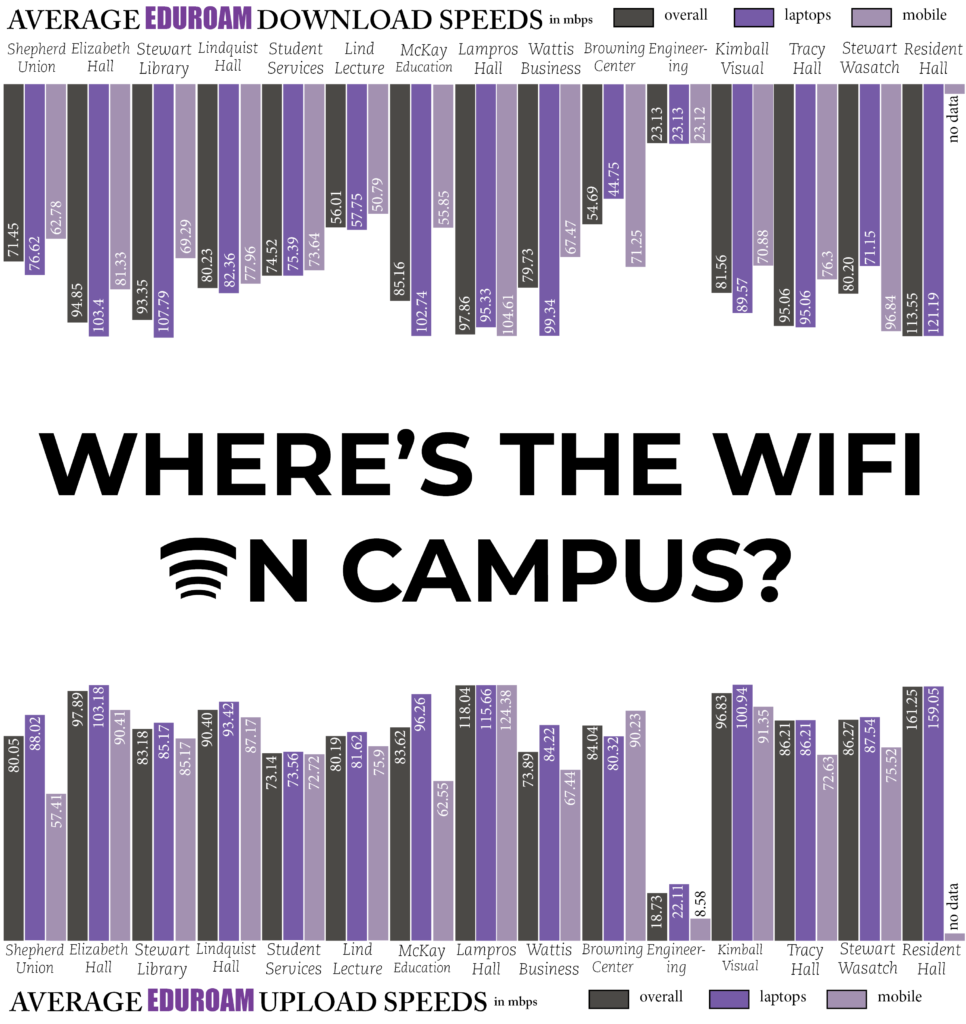

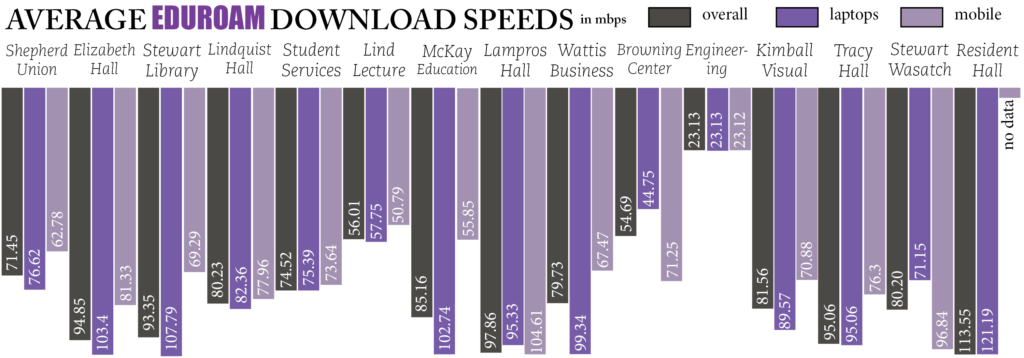

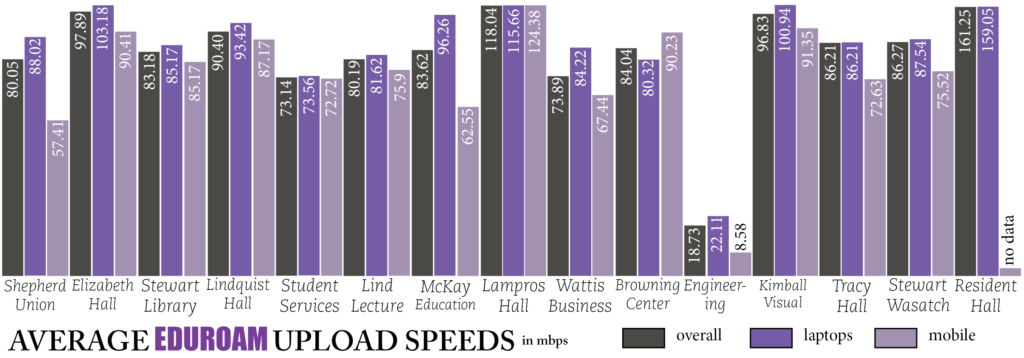

Over the last four months, The Signpost’s staff went to every building and tested the Wi-Fi to highlight what the student experience really was on the day-to-day.

Throughout campus, there were a total of 242 responses. Starting in the Shepherd Union, there was an average download speed of 71.45 mbps and an upload speed of 80.05 mbps.

In Elizabeth Hall, there was an average download speed of 94.85 and an upload speed of 97.89.

In the Stewart Library, there was an average download speed of 93.35 and an upload speed of 83.18.

In Lindquist Hall, there was an average download speed of 80.23 and an upload speed of 90.4.

In the Student Services building, there was an average download speed of 74.52 and an upload speed of 73.14.

In Lind Lecture Hall, there was an average download speed of 56.01 and an upload speed of 80.19.

In the Kimball Visual Arts building, there was an average download speed of 81.56 and an upload speed of 96.83.

In Tracy Hall, there was an average download speed of 95.06 and an upload speed of 86.21.

In the McKay Education building, there was an average download speed of 85.16 and an upload speed of 83.62.

In Lampros Hall, there was an average download speed of 97.86 and an upload speed of 118.04.

In the Wattis Business Building, there was an average download speed of 79.73 and an upload speed of 73.9.

In the Browning Center, there was an average download speed of 54.69 and an upload speed of 84.04.

In the Engineering Technology building, there was an average download speed of 23.13 and and average upload speed of 18.73.

In the dorms, first in Stewart Wasatch Hall, there was an average download speed of 80.2 and an upload speed of 86.26. In Resident Hall, there was an average download speed of 113.55 and an average upload speed of 161.25.

Speed tests measure the maximum speed of the current connection on a device, and they measure the total available bandwidth the Wi-Fi could utilize at that given moment in that building on campus. Bandwidth is the capacity of the network to transmit data to or from the information super highway of the internet.

Bandwidth breaks down to be like any other pipe. It can only transmit up to the total capacity that has been allotted to the Wi-Fi network, just like a water pipe cannot carry more volume than its size.

The download speed is the capacity the network has to pull information to itself — how fast it can Google something, pull up a document or stream a video. The more megabits per second available, the faster it can bring in data because it can utilize as much of the connection as it needs.

The upload speed is how much bandwidth there is to put something on the internet or over the radio waves of Wi-Fi — think Zoom conferences or submitting assignments on Canvas. The same is true for uploading as downloading: typically the higher the mbps rate, the faster something is able to be uploaded.

The measurement used in these cases is mbps, or megabits per second. A bit is a small packet of information, and a megabit is one million bits. For context, Zoom recommends 1-4 mbps per users, or more if there is screensharing or with everyone’s video on, and Netflix recommends at least 15-25 mbps per show being streamed.

The importance of having 242 responses in total breaks down to representing nearly 1% of the campus population, which is ideal when surveying for most populations as large as Weber State.

As part of the data collected, the types of devices were collected in the responses, and there are some notable differences when accounting for types of devices. Consistently, PC and android devices had much lower download and upload speeds than their Apple counterparts.

For instance, in the Student Services building, a PC laptop had a download speed of 31.92 and upload of 28.5, while the Macs tested in the building had an 82.64 average download speed and an 81.07 average upload speed. This was relatively consistent throughout all the results.

Almost all mobile devices were more than 20 mbps slower than a laptop on campus, but android and iPhones typically were very similar, and there was not enough data to compare the two.

“It’s picky about what devices it likes to connect to,” Krogue said. “I didn’t have any trouble downloading the certificate and accessing the Wi-Fi on my laptop, but after a few weeks of accessing it on my phone, it just stopped working altogether.”

What is concerning about the slower speeds on PC laptops is most of the computers students have available to rent on campus are PCs. For students who cannot afford a laptop and need to rent one, they are experiencing reduced speed — in some cases, dramatically so.

Secondarily, Macs are much more expensive than a PC, so students who cannot afford the high-ticket price of a Mac are also experiencing a lower-quality experience with the Wi-Fi all around.

While the tested speeds often qualify as good or even great internet speeds when you’re considering a home Wi-Fi, this does not account for the number of students trying to access things at the same time, especially when taking into account high-resolution video streaming, gaming or Zoom meetings during peak times in the dorms or other common hangouts on campus.

Weber State’s internet service provider is the Utah Education and Telehealth Network and connects with a 10 gigabit capacity, which includes all internet usage on campus. According to Karras, the university averages a total usage of around two gigabits per second, or 2000 megabits per second.

It seems like there should be enough Wi-Fi to go around, particularly after looking at the speed tests, but the tests cannot account for other users on the internet and their activity or when or what peak times will look like.

For example, in Stewart Wasatch Hall, if more than four students were attempting to log on to Zoom in the given area all with videos on with another two or three students watching YouTube or Netflix, it is very likely they would have issues with buffering or with their Zoom calls.

This breaks down to mean that depending on the time of day, there may or may not be enough bandwidth, assuming the device in question is getting the maximum bandwidth as tested, for an entire class of students to be on Zoom at the same time in the same location without noticing a significant difference.

“We definitely saw a lot of frustration reflected from the students,” Krogue said. “We directed most of them to campus IT services, so we weren’t hooking people up ourselves. We definitely got a lot of questions and concerns and feedback from students that they were struggling with it.”

Overall, the new upgrades have not changed the everyday experience for students, other than creating a new and confusing system for students to log onto, even if it is providing more security behind the scenes.

“I personally am not a fan of the switch,” Krogue said. “I understand that no system lasts forever and sometimes you have to make updates, but it definitely did not go very smoothly for myself and for the majority of people that I’ve talked to.”